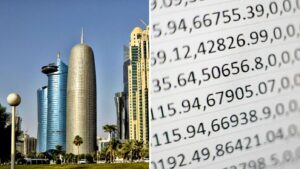

Separated by more than 2,400 years, two small coins quietly share the same watchful face—an owl whose gaze has endured the rise and fall of empires, the evolution of economies, and the passage of civilizations. One was struck in ancient Athens around 400 BCE; the other entered circulation in 2002, when Greece adopted the euro.

The ancient coin is the famous Athenian silver tetradrachm, one of the most influential currencies of the classical world. Bearing the owl of Athena, goddess of wisdom and protector of the city, the coin became a symbol not just of wealth, but of knowledge, vigilance, and civic identity. These tetradrachms financed trade, warfare, and daily life across the Mediterranean, circulating so widely that many merchants accepted them without even weighing the silver—an extraordinary level of trust in an ancient economy.

The owl was not chosen for decoration. In Athenian culture, it represented sharp sight, intelligence, and constant awareness—qualities the city-state proudly associated with itself. Over time, the image became inseparable from the idea of Athenian power and intellectual authority, turning a simple coin into a political and cultural statement.

More than two millennia later, the same owl reappeared on the Greek €1 coin, deliberately modeled after the ancient tetradrachm. When Greece joined the eurozone, designers chose to visually link the modern nation to its classical heritage. Though the metal, monetary system, and global economy had changed completely, the owl remained almost unchanged—an intentional echo of antiquity in everyday life.

Historians and numismatists point out that this continuity is exceptionally rare. Few countries have maintained such a direct visual connection between ancient and modern currency, especially across such an immense span of time. The coin serves as a reminder that money is not merely a tool for exchange, but also a carrier of memory, identity, and collective history.