In what could become one of the most important milestones in modern physics, researchers at Stanford University have developed a quantum device that operates at room temperature, potentially removing the biggest obstacle standing in the way of practical quantum computing.

Until now, quantum computers have required extreme cooling — close to absolute zero (-459°F) — because quantum bits, or qubits, are extraordinarily fragile. Even slight heat causes them to lose their quantum state, forcing scientists to rely on massive, expensive refrigeration systems that limit scalability and real-world use.

That barrier may finally be falling.

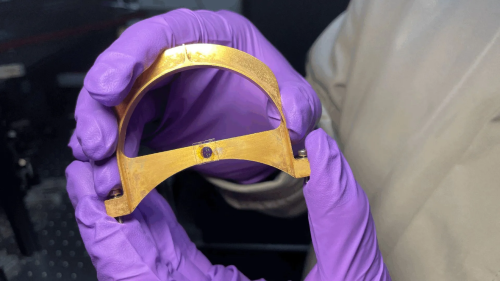

Led by Professor Jennifer Dionne and Dr. Feng Pan, the Stanford team has created a nanoscale quantum device that remains stable without any cryogenic cooling. Their work, published this month in Nature Communications, marks a major shift in how quantum systems can be built and deployed.

The breakthrough relies on a carefully engineered structure made from molybdenum diselenide, a two-dimensional semiconductor, placed on a patterned silicon chip. The silicon surface generates what scientists call “twisted light” — photons that spiral in a corkscrew-like motion. When this spinning light interacts with electrons in the material, it transfers angular momentum, locking electron spins into stable quantum states.

In simple terms, the researchers found a way to protect qubits from thermal collapse, even at room temperature.

Unlike most experimental quantum systems, this device is not just theoretical. The team has already demonstrated a working prototype, showing that quantum states can remain intact without refrigeration. This dramatically lowers costs, complexity, and physical size — opening the door to widespread adoption.

The implications are far-reaching. Room-temperature quantum devices could enable unhackable quantum communication, next-generation cryptography, beyond-classical computing power, and ultra-precise sensors for medicine, navigation, and materials science. Crucially, all of this could happen without the massive infrastructure that currently restricts quantum technology to specialized labs.

According to the researchers, the next phase will focus on refining performance and reliability. They estimate five years to integrate this technology into early quantum networks, and ten or more years to miniaturize it for everyday devices.